Webinar

Food Insecurity & Growing Concerns During COVID-19

Time & Location

Prior to COVID-19, it was estimated that 1 in 9 Americans were food insecure and lacked consistent access to enough food and nutritious options, including 11 million children. Food insecurity, while tied to poverty, is also impacted by other confounding social determinants of health, including access to transportation, housing and social isolation. As Americans practice social distancing and quarantine, many are faced with new challenges accessing and affording food.

This webinar brought together experts to provide insights on the longstanding issues surrounding food insecurity in the United States and how these issues have been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Speakers discussed:

- The evolution of food insecurity in the US and how it impacts many vulnerable communities

- How a national hunger relief organization is responding to the crisis and building partnerships to help communities secure the resources they need

- A health plan’s commitment to addressing food insecurity and how they are responding to the needs of their community

Caitlin Ellis (00:00:00): Good afternoon. I'm [Cait 00:00:02] Ellis, Program Manager at the National Institute for Health Care Management Foundation. On behalf of NIHCM, we want to extend our sincere thanks to healthcare frontline and essential workers for keeping us safe during this time.

Caitlin Ellis (00:00:15): This is a challenging time and our goal today is to share information and evidence-based strategies to address food insecurity in the United States.

Caitlin Ellis (00:00:24): In 2018, 11% of the population was food insecure. Now, as Americans practice social distancing and quarantine, many are faced with new challenges accessing and affording food.

Caitlin Ellis (00:00:37): Recent surveys found that 38% of households and 20% of children are now experiencing food insecurity. Additionally, it is well documented that a lack of access to enough nutritious food has a large impact on an individual's physical and mental health.

Caitlin Ellis (00:00:51): COVID-19 is exacerbating existing access challenges. It is also impacting how food is being produced and distributed. To explore short and long-term strategies to address these challenges, we are pleased to have a prestigious panel of experts with us today.

Caitlin Ellis (00:01:10): Before we hear from them, I want to thank NIHCM's president and CEO, Nancy Chockley and the NIHCM team who helped to convene this event. You can find biographical information for all of our speakers on our website, along with today's agenda and copies of slides. We also invite you to live tweet during the webinar using the hashtag food insecurity.

Caitlin Ellis (00:01:32): I am now pleased to introduce our first speaker, Dr. Daphne Hernandez. Dr. Hernandez is the Lee and Joe Jamal Distinguished Professor and Associate Professor at The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.

Caitlin Ellis (00:01:44): She's a developmental psychologist and examines health disparities resulting from poverty-related issues with a focus on maternal and child health and low-income Hispanic immigrant families. Her extensive and diverse work gets her the unique perspective on how food insecurity impacts communities. We are so grateful that she is with us today to share her insights. Daphne.

Daphne H. (00:02:07): Thank you, Caitlin. Today, I will be discussing how food insecurity has impacted communities as a result of COVID-19. Daphne H. (00:02:23): I'll briefly talk about, provide a background on food insecurity and how it impacts individuals, the trend, who has been impacted the most in relation to COVID-19. And then I will discuss how COVID-19 has changed how we view food access and food assistance programs, and then end with some strategies on how to reduce food insecurity. As I discuss these topics, I'm hoping that you will see how COVID-19 has highlighted significant disparities.

Daphne H. (00:02:58): Food insecurity is the lack of access to reliable and consistent access to food for a healthy lifestyle. Why was a concern about how food insecurity impacts others is because it has negative implications for children and adults.

Daphne H. (00:03:15): Specifically, we have observed greater absenteeism among children. These children also experienced greater attention and behavioral problems. We know that attention and behavior problems can lead to academic failure. Academic failure then puts individuals at risk for dropping out of school and then the cycle of poverty continues.

Daphne H. (00:03:38): Long-term consequences include, less healthy dietary intake, which is associated with higher risk for obesity and diet sensitive chronic diseases such as diabetes. These negative health implications have been seen in adults. We've also seen high rates of depression and anxiety among adults. So in the end, food insecurity does have a damaging effect for everyone.

Daphne H. (00:04:07): As it was just mentioned, the USDA 2018 pre-COVID estimates indicated that 11% of households without children and 14% of households with children experience food insecurity. I would like to note that this was an all time low. Unfortunately, now COVID has presented different statistics.

Daphne H. (00:04:32): 20% of households with children, according to the Brookings-Hamilton Project are experiencing food insecurity and this is based on a two question screener. Then there is work by Dr. Kevin Fitzpatrick and his colleagues at the University of Arkansas and they use the 10 item USDA scale to estimate that 38% of individuals regardless of household composition are experiencing food insecurity.

Daphne H. (00:04:59): While both of these studies have different items they are using to estimate the rates of food insecurity, both studies are tracking similarly and indicating that food insecurity is on a dramatic rise.

Daphne H. (00:05:14): To provide you a historical perspective of what the last time we had a dramatic rise in food insecurity, I will refer back to what occurred during the Great Recession.

Daphne H. (00:05:25): Food insecurity was at 15.8% in 2007 and then started to increase to 2008 as a result of the recession that began in December 2007. The recession technically ended in 2009 and Congress reacted to the economic downturn by passing the 2009 Recovery Act, which increased SNAP benefits between 2010 and 2013. While the increase in SNAP benefits did prevent rates of food insecurity from further escalating, you can see that we maintained at a 20% rate.

Daphne H. (00:06:06): We did not see a decline until 2015 where we declined the rate to 16.6%. And then it was not until 2018 that we saw food insecurity rates go below the pre-recession rate at 14%. So as we design policies to address food insecurity surges related to COVID-19, we need to take these practices into consideration.

Daphne H. (00:06:30): Now, we received several questions, great questions, from individuals that registered for this webinar and one of them was, "Why is there food insecurity in a country as wealthy as the US?"

Daphne H. (00:06:45): I realize it's hard to imagine that children in the US are living in food insecure households when we consider the number of food establishments that surround us and the number of food-related commercials.

Daphne H. (00:06:57): In Texas, where I'm located, there are over 43,000 restaurants in Texas, which ranks Texas as the third in the number of restaurants per capital. Therefore, if we're have that many restaurants, we have enough food for the United States.

Daphne H. (00:07:14): So contrary to other nations, the US does not suffer from food shortage or famine. We suffer from income inequality. In other words, poverty is the root cause of food insecurity.

Daphne H. (00:07:30): While low-income families are impacted by food insecurity, there are also two other types of families that are impacted. Those are the working poor families and families that live paycheck-to-paycheck. These are families that make too much money and are not eligible for public program participation. These families are unable to meet their basic needs such as shelter, utilities, food, clothing and medical care on a month-to-month basis.

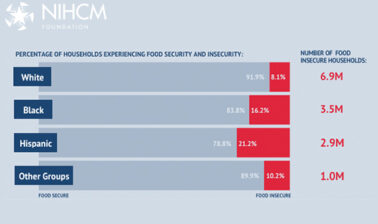

Daphne H. (00:07:57): They do adapt financial managerial strategies to deal with the economic pressure. For example, one month they pay rent and the other they forgo utilities, and the following month they pay utilities, but forgo rent. Many times the decision to pay a bill is based on services being cut off. Daphne H. (00:08:20): Further, there are some individuals that are impacted by food insecurity in a much greater way. This figure displays that Blacks and Hispanics are impacted by food insecurity more than Whites and other races.

Daphne H. (00:08:32): Blacks and Hispanics are also more likely to work in the service sector industry such as restaurants and food packing industry, which are now considered hazardous. Their lack of access to care and underlying health conditions among this population places them at greater risk for experiencing infection by COVID19.

Daphne H. (00:08:55): I will now discuss how COVID-19 has impacted how we view some food access and food assistance programs. Daphne H. (00:09:04): When States started to shut down we started to see some distribution challenges that were more related to hoarding than the lack of food in this country. Consequently, we saw bare food displays. However, this was only temporary and individuals that still had resources to access food could so during this time.

Daphne H. (00:09:26): We are now seeing more meals being prepared and consumed at home compared to eating out. While families may be saving more money on meals because of preparing and consuming their meals at home, they're also spending more on particular items when generic or less expensive brands are not available.

Daphne H. (00:09:48): We've also observed an uptick on online grocery shopping, which includes grocery delivery services and curbside grocery pickup services. Both of these types of services minimize the contact, which lowers the risk of infection.

Daphne H. (00:10:04): Congress has also responded to the economic downturn and made some changes to food assistance programs. All three programs that are listed here have seen additional funding being allocated to them to increase program participation.

Daphne H. (00:10:23): We've also seen the School Lunch Program restructured, so that children can access food. WIC participants are now allowed to enroll or re-enroll in WIC without visiting the clinic in person and postpone certain medical tests. Time limits associated with work requirements have been suspended for SNAP recipients.

Daphne H. (00:10:47): Now, I'll end with some strategies on reducing food insecurity. Daphne H. (00:10:54): There have been several proposals laid out on how to increase food access through the SNAP Program. Currently, there is a proposal to allow restaurants to accept SNAP benefits. This will provide an opportunity to invest back into the local community, but also provide low-income families to receive meals. This type of mutual benefit attempts to stabilize the economy. Each dollar of SNAP benefits that are spent during a downward economic downturn generates between $1.50 and $1.80 in economic activity.

Daphne H. (00:11:32): There is also proposals to increase the minimal and maximum SNAP benefits. There is a proposal to increase the minimal SNAP benefit from $16.00 to $30.00 and a proposal to increase SNAP maximum benefit by 15%. Increasing minimal and maximum benefits would help families with economic hardships, but also help them prepare for disasters or help them prepare to have enough food in the house in the event that they got sick. For low-income families, it's difficult for them to buy in bulk or at two weeks at a time as they do not have the disposable income to do so.

Daphne H. (00:12:10): As mentioned earlier, SNAP allotments were increased after the Great Recession from 2010 to 2013, so this reconation is not unprecedented. There is also a proposal to suspend all SNAP administrative rules that would terminate or cut benefits. Daphne H. (00:12:31): I would like to also provide further strategies on what can be done at a national or even local level. Currently, there is not a way to use WIC or SNAP benefits in online grocery shopping, requiring recipients to physically go in stores. There are 38 million SNAP recipients. This means there is 38 million SNAP recipients walking the aisles increasing their exposure to coronavirus for a group that has limited access to healthcare and probably has underlying health conditions.

Daphne H. (00:13:02): I will note that Texas and other States have recently signed up for a pilot program that would expand access.

Daphne H. (00:13:10): Second, I would like to see WIC and SNAP benefits be used towards cleaning supplies and PPE, which is currently not allowed. Cleaning supplies and PPE, which is currently in high demand, may not be something that low-income families have in abundance. We need to consider the needs of these individuals and what we're asking of all individuals in terms complying to CDC guidelines.

Daphne H. (00:13:40): Last, there are a couple more things that I would like to suggest. My research has indicated that one of the biggest challenges for families is having to decide whether to have gas in their car or food for a week. Many of the low-income individuals are essential workers and are in need of gas and to get to work. And that also to attend food distributions to feed their families. Thus, a gas or transportation voucher is recommended.

Daphne H. (00:14:08): As previously mentioned, SNAP benefit allotments were increased for three years after the Great Recession, but we did not see declines in food insecurity until six years after the recession ended. Moving forward, SNAP benefit allotments need to be increased. In addition, the increase of allotments need to be maintained for a minimal of three years, but perhaps consider six based on prior historical trends.

Daphne H. (00:14:31): After a pandemic subsidies, these families will need to continue to receive additional food assistance as lost wages will put a financial strain on their pocketbook.

Daphne H. (00:14:42): And last, in January of 2020, the USDA made two proposals that should not occur. The first one is a proposal to make it harder for families to qualify for SNAP. The second one is a proposal where there it would make the School Lunch Program less healthy. Both of these proposals should not occur at a time when families will need these programs and proper nutrition is needed to maintain immunity towards illness.

Daphne H. (00:15:10): Last, I would like to provide a long-term strategy to reduce food insecurity. And that strategy is a holistic approach to food insecurity because food insecurity is just not about food and there is a need to address social determinants.

Daphne H. (00:15:24): My research along with others have indicated that individuals that have difficulty accessing food also have difficulties paying their utilities, rent, and other bills. I would like to see a holistic program that addresses both food and housing insecurity together as this would be a more effective strategy to reducing both types of hardships simultaneously.

Daphne H. (00:15:47): I would like to thank the Scholars Strategy Network for helping me prepare for today's talk. If you would like to read more about my policy recommendations, especially about the holistic approach to reducing food insecurity, it can be found on their website. I'm also open to discussion further on the topic of food insecurity with others and how we may collaborate during this time. Thank you.

Caitlin Ellis (00:16:11): Thank you, Dr. Hernandez for helping us all understand more about the recent history of food insecurity and the trends and the types of solutions both long and short-term that could help make an impact for these individuals and families.

Caitlin Ellis (00:16:24): Our next speaker, Gita Rampersad is the Vice President of Health Care Partnerships and Nutrition at Feeding America. Gita can provide an up close look into Feeding America's longstanding work to improve access to quality food and how the organization is responding to COVID-19. Gita.

Gita R. (00:16:44): Thanks a lot and good afternoon, everybody. I am here on behalf of Feeding America's national network of food banks to discuss food security and COVID-19.

Gita R. (00:17:03): I'd like to begin by talking about hunger in America before COVID-19. This has already been touched on by Dr. Hernandez, but this is also the way Feeding America frames hunger. The USDA estimates that 37 million Americans struggle to afford the food they need. This includes 11.2 million children and 5.5 million seniors. Like COVID-19, hunger does not discriminate. We see that hunger affects every community in this country.

Gita R. (00:17:45): This a map from our Map the Meal Gap Project at Feeding America that shows the rates of food insecurity across the country. Although, food, hunger does not discriminate, we do see that there are areas that are more highly concentrated when it comes to food insecurity, particularly in the South, the Southwest and the Pacific Northwest regions.

Gita R. (00:18:13): This is households that are experiencing food insecurity, and the darker the green the higher the food insecurity rates. Though showing that there is a wide variation by county, but if you were to pepper in households with children, just imagine this map with all of the shades of green going darker, but still staying about the same in the way the food insecurity rates are distributed. With that in mind, we have to keep in mind that it's important to address food insecurity using an equity lens.

Gita R. (00:18:53): Because everybody experiences food insecurity in a way that forces them to make tough choices, we see that other social determinants and healthcare can be exacerbated by hunger.

Gita R. (00:19:07): For example, in a, we wrote a client survey, annual client survey, and our clients at Feeding America report that 59% have had to choose between paying for utilities or food, 67% has had to choose between paying for transportation and food, 66% have had to choose between paying for their medicine or food and 57% have had to choose between paying for housing and food.

Gita R. (00:19:35): Because of the audience today, I've highlighted the 66% of having to make a choice between medicine and food. This should never have to be a choice. None of these should have to be choices that anybody makes, but this is a reality and this is a reality pre-COVID-19.

Gita R. (00:19:58): Because of these tough choices, we can see that hunger creates an unhealthy cycle. Again, going to back to our client survey, we have seen that because when budgets are stretched thin, oftentimes this leads to the purchase of inexpensive, unhealthy processed foods.

Gita R. (00:20:16): 79% of our households in our network have reported having to purchase these types of food products to be able to stretch their budget. Once that happens the more unhealthy and inexpensive processed foods that's eaten can cause fluctuates in weight and in blood sugar, which then in turn lead to diet-related disease such as high blood pressure, heart disease, and diabetes then obesity, which then sends us into an increased healthcare expenditure problem. So we have seen significant increases to the cost of healthcare.

Gita R. (00:20:55): But, I do want to just point out that of this survey, in the survey, almost 60% of our households in our network have reported a member with high blood pressure and a third of our households reported a member with diabetes. So these are both conditions that come with dietary restriction and special diets and oftentimes, that may not be entirely possible when they have to stretch a budget.

Gita R. (00:21:24): As I mentioned, food insecurity leads to higher healthcare costs. We've seen this. Feeding America did a study with the University of California San Francisco and we noticed that the food insecurity leads to more treatments around chronic disease, more hospitalizations, higher readmissions rates and to the tune of about $2,000 per person per year, which amounts to over 77 billion dollars in additional healthcare costs per year. So it's really taxing on the healthcare system.

Gita R. (00:22:09): I'd like to pause for a minute and just talk about a bit about Feeding America and who we are for those of you on the call that may not be familiar with a food bank network.

Gita R. (00:22:21): We are a network, a national organization with a network of over 200 member food banks reaching every county in the country and over 60,000 food pantry and meal program partners. Combined, we are able to provide more than 45 million Americans annually with food assistance.

Gita R. (00:22:47): This slide shows that we have been experiencing a decade of growth despite the fact that food insecurity rates were up, until very recently, on the decline. We have seen an increase in the amount of people that we are serving and the amount of meals that we have had to provide. So the white is 2007 and the orange is 2017.

Gita R. (00:23:17): Again, I'll mention that we are in every county of the United States, Washington DC and Puerto Rico. This is a map of our member food banks to date. On our website, we actually have an interactive version, so that if you click on any state, you can be directed to any food bank that is serving residents of your state.

Gita R. (00:23:43): Now, my background is in health and healthcare. And so, when I came to Feeding America to oversee their healthcare partnerships and nutrition work, this is a learning curve for me. I thought, maybe it would be also important and helpful to provide a slide that describes how food banks were.

Gita R. (00:24:06): Initially, about over 40 years ago, food banks were created as a community solution to the challenges of poverty, hunger and food waste. The infographic at the bottom shows that surplus food is acquired either by purchase or by donation and is then sourced to local food banks. Local food banks in turn package the food and distribute it to over 60,000 of our partner programs around the country allowing one in seven Americans to be served. So this is a good way for me to understand the food bank model.

Gita R. (00:24:44): But I will say, that food banks are now addressing a lot more than just food access and food security. We are tackling many of the social determinants of health plus also engaging in some healthcare activities.

Gita R. (00:25:03): Many of our food banks offer job training. We offer safety net resources, enrollment such as SNAP and children's health assistance or, sorry, food assistance. We also provide enrollment support for Medicaid and Medicare.

Gita R. (00:25:21): We are engaged often in healthcare screenings such as diabetes screenings and high blood pressure screens. Food banks offer voter registration. We also provide in some food banks a level of case management, so we have referral systems between our healthcare partners in our food banks and it allows us to follow-up with our clients to see how they are managing their chronic conditions.

Gita R. (00:25:47): We are also engaged in educational partnerships because as Dr. Hernandez mentioned, part of the food security problem lies in trying to break the poverty cycle. And so, we are doing our part to address some of these additional social determinants. And of course with COVID-19, we can add some more to the list here.

Gita R. (00:26:14): I do want to mention that even though Feeding America is not considered a disaster relief organization, we do lead in times of disaster. Right now, our Disaster Preparedness Department is gearing up for hurricane season. It's something we don't know what to expect, but it's not always, it never sounds good. So at the same time that we are juggling our response to COVID-19, we are also thinking about what Mother Nature is going to bring in the form of a hurricane season.

Gita R. (00:26:42): But, we do have some incredible resources that we are able to offer to communities and to try to address issues in times of disaster, and that includes over 10 million square feet of warehouse space, over 2600 vehicles in a fleet that are ready to respond and close to 90% of our food banks already operate mobile pantry programs that deliver food into hard to reach communities. [inaudible 00:27:11] can be operationalized to and mobilize around disaster.

Gita R. (00:27:17): I don't want to advance to the next slide without saying that we do count on over two million volunteers and that, typically, to help us in our food bank operations. But of course, this has all changed given the current landscape.

Gita R. (00:27:43): For now, I'd like to talk about COVID-19 and really what we're seeing in terms of impact, how we've been able to respond and just briefly touching on what recovery would look like. To be honest with you, we are so still, like right now, focused in on our respond that it is, it's hard to imagine recovery, but we do know that it's coming. So we are beginning to prepare for that, but we are very much still in the response phase.

Gita R. (00:28:13): Initially, Feeding America's response to COVID-19, we identified an immediate need for food and for money from our food banks, so we launched a COVID-19 Response Fund, which is a national food and fundraising effort. Gita R. (00:28:31): To date, money-wise, we have raised over 200 million dollars and this continues to grow. This has allowed us to provide emergency grants to food banks to support their local response efforts and we have already pushed out of that 200 plus million, we've pushed out over 100 million into emergency grants.

Gita R. (00:28:55): We have a member grants department that looks at the need every week, or every other week for food banks in terms of how much food they have left to, in their inventory, how many more weeks they can sustain their operations and we tailor our grants to meet the individual needs of our food banks.

Gita R. (00:29:16): We've also built an inventory of emergency food banks, hundreds of thousands of food, I'm sorry, food boxes, hundreds of thousands of them that are to be distributed to food banks across the country. We did this initially in the first week or so of the response before we were able to get a handle on some of the sourcing and distribution adjustments that needed to be made. But obviously, hundreds of thousands of emergency food boxes is not going to cut the needs that we're seeing, but that was at one of our initial response actions.

Gita R. (00:29:50): We are able to safely distribute food, non-food and household items like cleaning supplies, diapers and personal care products as part of the response. Unfortunately, we have seen a drop in our retail donations. Our cleaning products is one of the items that we see is very hard to come by, by now. So right now, we are focused on providing food and cardboard boxes out to our food banks.

Gita R. (00:30:25): Feeding America is in the middle of conducting its impact assessments to see how COVID-19 is presenting new challenges to our communities. What we are estimating is that over 17 million more people will need food assistance as a result of this pandemic. That means that to us that is a 46% increase in demand. And so, this is quite a number for us, but we are responding. We're continuing to respond. But, that is the reality that we have moved from 37 million to over 50 million in a matter of weeks.

Gita R. (00:31:09): I wanted to share this graph with you that's been circulating. It's part of a survey that we take with our food banks. We were able to track the amount of pounds of food that Feeding America sourced to our food banks weekly from over the same time period, so from March 8th through April 26th the lower line is 2019 and the orange line at the top is 2020. And as you can see, there is a market increase in the amount of pounds that has been sourced to our food banks.

Gita R. (00:31:51): Likewise, this is a graph that shows the distribution by the numbers. In other words, the pounds of food that have been distributed by food banks out into the community on a weekly basis. And as you can see, I only have numbers up until the end of April. But the last week in April, we saw a jump from 130 million pounds up to 171 million pounds just in a week.

Gita R. (00:32:20): Another reality that we are facing is the stories that we're hearing from our network. We get these network testimonials that are really, that really pull at your heart strings. I've included a couple of them here today because it really does put into perspective the human side of what's going on.

Gita R. (00:32:38): The fact that there are people that are visiting food banks that are saying, "Hoarding is the last thing that we're thinking of right now. We won't even get by past the next two days. We don't know what we're going to do." And of course, I'm sure everybody has seen the news stories with all the thousands of cars lined up at food banks to receive food and it's not getting any better.

Gita R. (00:33:01): Additionally, we have to consider that there are a lot of these families that have special needs. There is another testimonial here talking about someone with disabilities and people who have special diets, what types of challenges they're facing when they stand in line to get in a grocery store for hours and then they can't get what they need because they go to the aisle that they need and there is nothing there. So these are some of the stories that we're hearing that are really putting everything into perspective for us.

Gita R. (00:33:37): In addition to the increased demand for charitable food, we have seen declines in donations, as I mentioned, retail donations in particular. We are also seeing an increase in operating and distribution costs at our food banks along with decreased volunteer support.

Gita R. (00:33:58): We are conducting a bi-weekly survey with all of our network food banks. The CEOs respond, or some of their senior leadership responds to us to help us understand what the increasing needs are across the network.

Gita R. (00:34:14): As we had mentioned before, 98% of the food banks have reported an increase in demand with an average increase of 63%. 95% percent of the food banks in our network have reported an increase in operating expenses, expenses with an average of 31%. We've also seen almost 60% of food banks report a decrease in inventory from the same time as last year due to the increased need.

Gita R. (00:34:41): And almost 70% of food banks are now accepting additional volunteer support or showing a need for volunteer support. Many of our volunteers are seniors and seniors are high risk, in a high risk group during this pandemic, so in order to protect their health and safety they are not always encouraged to come.

Gita R. (00:35:03): There is just a lot of new challenges in how we have to operate these days in terms of social distancing and our distribution models have been adjusted to drive-thru and delivery rather than having people come in and purchase them directly. So there is a lot of new challenges, but we continue to see the needs rise for volunteers and other things.

Gita R. (00:35:32): I guess to put it in perspective when it comes to financially, we look at, we are looking at, and this is a very hard pill to swallow is, we are looking at needing an estimated 1.4 billion dollars over the next six months, just the next six months, to provide food to people facing hunger. Now, this is including the support that we have and are relying on from the federal government. But nonetheless, 1.4 billion is a number that is very hard to wrap your head around, I would image. It certainly is for me. But that's our reality right now and that's just six months.

Gita R. (00:36:13): There are new emerging concerns that we are typically, as a food bank network, not at the top of our list when we're talking about emerging concerns, but there are new workplace health and safety concerns that come about because of this pandemic. And so, we are addressing these workplace, health and safety concerns along with a much higher need for mental health and well-being resources.

Gita R. (00:36:41): People are really, really feeling the strain of this in various ways. Almost everybody has a personal connection to the pandemic at this point, so these mental health services are becoming more and more critical to be able to provide to our network.

Gita R. (00:36:58): We are also focusing more on our high risk populations, our seniors, our food bank members that have, that serve a lot of diabetic populations and immunocompromised populations.

Gita R. (00:37:14): We're also seeing new challenges in our rural communities. I mean, rural communities already have their, have existing challenges pre-COVID-19 and now they have even more challenges about how they can access food and of course, even healthcare.

Gita R. (00:37:31): We are seeing, as Dr. Hernandez pointed out before, more glaring racial disparities emerging from this, not only in the way COVID is impacting infection and death rates in different, for different races, but also in food access. There has always been a higher rate of food insecurity for Blacks and Hispanics and now that is exacerbated by the pandemic.

Gita R. (00:37:59): And finally, we are really turning our attention to the healthcare frontline staff and their, and the issues that they are facing. We are concerned about their health and safety and their ability to get food because many of these staff are not leaving the hospital for extended periods of time, so that is something that Feeding America has turned its attention to.

Gita R. (00:38:25): Part of our COVID-19 response based on those emerging concerns includes a health and nutrition subset of the response. We've stood up a public health task force at Feeding America for the first time, which is, consists of three work groups. One is addressing workplace health and safety, another is addressing mental health and well-being, and the third is addressing high risk and health disparities. We are providing food banks with emerging practices to tackles some of these concerns. We're also providing technical assistance.

Gita R. (00:39:03): I got to say, we can't do this alone. We're working with our healthcare partners such as Anthem and other payers and health systems and [inaudible 00:39:12] the national associations in academia really to provide a strength in numbers approach to how do we address the health and nutrition concerns of our communities.

Gita R. (00:39:22): We're also engaging in new research studies to address the epidemiology, the economic trends, what's happening with children. I think there is about another additional seven million children are going to be food insecure as a result of COVID-19. We're looking at disparities. We're looking at how we can provide tools, so that people can manage their chronic disease during a pandemic.

Gita R. (00:39:49): And then finally, again, we are looking at the frontline. One of our [inaudible 00:39:53] are project is, we are participating in the Feeding the Frontline Initiative with The Aspen Institute and World Health Kitchen to help to develop health and safety protocols. But I think maybe some of you have noticed on the news, food banks are taking it on their own personal crusade to feed the frontline just by delivering food to some of these healthcare, frontline healthcare workers.

Gita R. (00:40:20): This slide is just a sample of the public health resources that we are producing and these one page flyers, so that people can get an understanding, a quick and easy understanding of some of these new concepts. Not very many of our food bank members were aware of the social distancing and the rules of social distancing. There is a need to upgrade our cleaning and disinfectant practices. So these are two examples of changing that we've had to make on the fly, but we've tried to put them out there in easy, user friendly formats, so that they can be adapted very easily given the fact that every week brings a new surprise.

Gita R. (00:41:04): And just before I end, I'd like to just touch on the COVID-19 recovery. We're looking at ongoing supply chain shortages, not necessarily food shortages. There is some breaks in the supply chains that are really causing challenges, presenting challenges and causing us to think through how we can overcome some of these shortages. One way is by building a comprehensive food purchase initiative.

Gita R. (00:41:32): The other major way we are moving into recovery is the Government Relations Team at Feeding America is working tirelessly to advocate on the Hill for the needs of hungry families. As Dr. Hernandez pointed out, we are writing a letter to Congress to advocate for a 15% staff increase. It is going to be a sign-on letter. If there is anybody on the call that's interested in signing on with their organization, please reach out to me after the webinar. I'm happy to discuss further.

Gita R. (00:42:07): And again, our team of experts in our national office are continuing to provide a range of resource and technical assistance. Oftentimes, this turns into a one-on-one phone call with a person from a food bank who is in distress just because of the amount of stress and trauma that is accompanying the work that they're doing.

Gita R. (00:42:31): But I never want to leave on a low note, so I'd like to leave on a high note and leave us with three key messages for recovery. That let's make sure that we don't lose sight of the fact that equity matters. This is not a one size fits all solution and we should always be leading with an equity lens.

Gita R. (00:42:50): Secondly, partnerships are essential, as I mentioned before, our partnership with Anthem. Anthem has been an incredible partner throughout this response period and it will continue to be a long-term partner in recovery and beyond. So partnerships are essential. We can not do this alone.

Gita R. (00:43:07): And finally, we always have to remember that brighter days are ahead. We always start our days at Feeding America with some sort of group message around hope and healing. That's something that we can't lose sight of, so brighter days are ahead. Thank you for allowing me to present and I welcome questions later on.

Caitlin Ellis (00:43:25): All right. Thank you so much, Gita for sharing your important work and for highlighting the importance of partnerships and collaborations in addressing these critical healthcare challenges.

Caitlin Ellis (00:43:38): Under the leadership of president and CEO, Curtis Barnett, Arkansas Blue Cross Blue Shield is advancing a comprehensive approach to address food insecurity in communities across Arkansas, including providing critical funding to help organizations supporting communities impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Caitlin Ellis (00:43:56): To hear more about these efforts, we are now joined by Rebecca Pittillo, Associate Director at Blue & You Foundation for a Healthier Arkansas. Rebecca.

Rebecca P. (00:44:06): Hi and good afternoon to everyone. We're going to start with, get these slides going, a history and just about Arkansas in general where food insecurity is concerned.

Rebecca P. (00:44:24): One in five Arkansans struggle with hunger. Many of them don't know where their next meal is going to come from. Arkansas ranks in the category of very low food insecurity at 8.1%.

Rebecca P. (00:44:38): So to give you an idea of what that means, households that fall into this USDA category had more severe problems experiencing deeper hunger and cutting back or skipping meals on a more frequent basis with both adults and children. Arkansas ranks second in the number of people facing food insecurity, according to a more recent report, 19.7%.

Rebecca P. (00:45:04): Arkansas is ranked 6th in senior hunger nationally. An estimated 240,000 plus Arkansans over the age of 60 are food insecure. And again, this is on a good day. This is before COVID-19.

Rebecca P. (00:45:27): Committed to the cause. For more than seven decades now, Arkansas Blue Cross Blue Shield has been committed to truly providing a peace of mind to our members through the obvious nature of our business. But, we've also invested in our communities to try to improve the overall health of our state's citizens.

Rebecca P. (00:45:49): There are many factors that combine to affect the health of individuals in the communities that we serve. There is an increased recognition of the influence social determinants have on a person's overall health, economic stability, neighborhoods that people live in and their physical environment, their education, and communities and of course, food or the lack thereof. So we're looking beyond just the place where medical services are provided in an effort to positively impact health early on.

Rebecca P. (00:46:25): In the past few years, we have made a concerted effort to work with organizations in the state that are committed to helping people have access to nutritious food. Feeding the most vulnerable Arkansans help give them a step toward better health and a better life.

Rebecca P. (00:46:43): In 2018, in celebration of our 70th anniversary, we worked with community organizations, businesses, churches and schools to prepare more than 1.1 million meals for local food pantries through our fearless food [inaudible 00:47:02]. In early 2020, we were approximately 20,000 meals away from surpassing our 20 million meal mark, so quite an accomplishment.

Rebecca P. (00:47:21): In support of our corporate commitment to good nutrition, our Blue & You Foundation for a Healthier Arkansas also has supported programs statewide that have begun to help bend the trend on hunger in the state.

Rebecca P. (00:47:36): Over the last 19 years, we've awarded 242 grants to help fight the battle of food insecurity in our state. These grants total more than 2.4 million dollars and support food pantries, cooking and shopping educational programs, community gardens, backpack programs for schools and afterschool programs, some are nutrition for children, and daily lunch programs and soup kitchens.

Rebecca P. (00:48:10): So that was all before COVID-19, so enter novel coronavirus. America and Arkansas are in shock at the sudden need for social distancing. Fear began to get a grip on our nation and the world, and our state was no exception. We've all seen the photos and the footage of fights over bathroom tissue and the disappearance of thermometers and bottled water from the shelves and all the hoarding of antibacterial hand gels.

Rebecca P. (00:48:44): Well, our food banks in Arkansas anticipated and began preparations for the worst situation possible. They began to order additional food from their usual resources, looked for new resources and stock up on proteins with more shelf life. They were making decisions like all organizations about how to serve their patrons while keeping paid staff, volunteers and their patrons safe.

Rebecca P. (00:49:21): We reached out to state leaders in the food insecurity space, already partners in the fight against hunger, to assess the needs. This is what we heard from some of our partners, The Arkansas Hunger Relief Alliance was already helping with most every aspect of feeding the hungry in our state. With heighten needs to protect people through social distancing, of course a practice needed to reduce the spread of COVID-19, but also a practice that pushes people further from the food sources needed, so issues there.

Rebecca P. (00:50:03): The Arkansas Foodbank working closely with Feeding America, the Arkansas Department of Health, the local school districts in 33 counties in Central and Southern Arkansas were sending thousands of emergency boxes to schools for kids to pickup trying to ensure children and families and seniors have access to the most basic necessities during this time. As in the case in many States, sometimes the only meals a child would get in any given day is through the schools. The food bank drew on three months of funding to get ahead of the impending demand.

Rebecca P. (00:50:39): The Pack Shack was seeing an escalating number of requests from an already demanding list of food pantries and new groups were starting to surface, out of work musicians and furloughed restaurants and hospitality industry workers. And so, since the process used to get meals packed at The Pack Shack involves lots of people working elbow to elbow in large spaces, the volunteer-driven method of meal packing had to be re-engineered.

Rebecca P. (00:51:10): The bottom line is, everyone needed funding and they needed it immediately. Already existing gaps were getting wider and the sense of urgency was real.

Rebecca P. (00:51:25): We recognize the tremendous needs created by COVID-19 and understood the importance of responding with great urgency. To support food insecurity, the Blue & You Foundation for a Healthier Arkansas gave $500,000 throughout the state by donating to the three large food distributions hubs that I previously mentioned, the Arkansas Foodbank, The Hunger Relief Alliance and The Pack Shack as well as the 17 United Ways of Arkansas who will all provide food to thousands of Arkansans.

Rebecca P. (00:52:03): We also understand that there are organizations who can help fill in the gaps that we might miss and so, we also provided $150,000 to the Arkansas Community Foundation that currently has a grant process open to nonprofits with food insecurity being a focus.

Rebecca P. (00:52:22): COVID-19 called for an urgent focus on how we approached our traditional grant season at the Blue & You Foundation for a Healthier Arkansas. We suspended our normal grants that are open for applications, in a normal year, January through July 15th. We opened the Rapid Response COVID-19 Grant Program.

Rebecca P. (00:52:55): We've earmarked 1.7 million in grants supporting nonprofit organizations that have been impacted by and are making the greatest impact on preventing the spread of COVID-19. The grants range from $5,000 to $150,000 are truly a rapid response in that we have been evaluating and awarding on a weekly basis and the grant process is more simple than it's ever been to apply.

Rebecca P. (00:53:25): The first week we had 52 grant applications come in, the second brought in 107 and the third, we had an additional 55 grants come in. So the need is just, it's overwhelming.

Rebecca P. (00:53:40): I make mention of these grants to also say that it was very telling to us the importance of our initial gift to food insecurity because many of the organizations that we were seeing coming in with these grant applications, they didn't have a primary or even secondary mission to feed people, but they were asking for funding for food.

Rebecca P. (00:54:11): When we made follow-up calls to the food hubs, it was evident that this was a long-term issue. To save a little time, I'll just share with you the report that we got back from the Arkansas Foodbank. Since our gift to the Arkansas Food Bank, they have seen a dramatic increase in need along with a complete shift in how they can best serve those in need.

Rebecca P. (00:54:43): The need to help first time users of the charitable food system is one of the shifts. They report that around 40% of their distributions are to new users. The sudden loss of employment and unemployment system being overwhelmed has left many stranded without income. And without unemployment support, these are families and individuals who have never been forced to use the charitable system before and have no idea even the questions to ask or what to expect.

Rebecca P. (00:55:21): The second shift is, in order to support social distancing, they've had to flip their model from a hand-on grocery store model to a drive-thru and pickup model with very little contact with clients. This has created a need for boxes and box packers, both of which require additional resources. They report that having the support of the community helps meet those demands and new models.

Rebecca P. (00:55:53): From the beginning of the pandemic in early March, the single focus has been to meet the needs of Arkansans no matter the change or the cost that it required. To date, the funds from organizations like Blue & You Foundation have allowed them to pack and distribute over 18,000 emergency boxes and distribute an additional two million pounds of food.

Rebecca P. (00:56:16): I'd like to share with you this very touching statement from the Arkansas Foodbank's CEO, Rhonda Sanders. She said that, "There are so many faces that stand out when I consider our work the past two months. One in particular always inspires me. In North Little Rock, we had a direct distribution using the drive-thru model. We only set aside a few boxes for those who lived close by the neighborhood and did not have a car. We were down to the very end of the distribution and there were only a few boxes left for cars and only one left for walk-ups.

Rebecca P. (00:56:58): An elderly lady walked up the sidewalk looking to see if she could get food. I took one of the last boxes and sat it on the ground where she could pick it up and maintain the adequate amount of distance from me. She began to cry and said, 'You have no idea what this means to me,' Rhonda Sanders continues, "I may not be able to completely walk in her shoes, but I can safely say that she also has no idea what it means to me to be able to provide her with a box full of food and of hope." Again, that's Rhonda Sanders, CEO of the Arkansas Foodbank.

Rebecca P. (00:57:49): Evaluating needs and next steps. We all recognize that COVID-19 has caused as great of an economic impact on our state of Arkansas as it has on health. But, as the State of Arkansas begins phase one of reopening, we're hopeful that those who were furloughed from their jobs and experienced job loss will get back to work in safe environments.

Rebecca P. (00:58:13): But, we also brace ourselves for the possibility of what comes next and what needs will arise. Because of this, we are continuing to evaluating needs as the grants come in and look to what our next steps will be to help Arkansans with what will surely be a long-term rebound from COVID-19.

Rebecca P. (00:58:37): I too would like to end on what I feel like is a very positive note, staying the course. Arkansas Blue Cross and Blue Shield has such an amazing team of employees, a little over 3,000 strong. We always say, when a need surfaces, they are the first to raise their hands to help volunteer and the first to reach deep in their pockets to support their fellow Arkansans. They are compassionate, committed and generous.

Rebecca P. (00:59:09): Every year, they participate in the annual Charitable Giving Campaign to support charities that address social determinants of health, including food insecurity. In 2019, they pledged more than $93,000 to organizations in our state, which was matched by the company. On average, they support more than 35 worthy causes and raise about $50,000 annually for various charities above the Giving Campaign that I just mentioned.

Rebecca P. (00:59:39): Arkansas Blue Cross and Blue Shield employees hold food drives throughout the year including the Summer Cereal Drive, which collects hundreds of boxes that are donated to food banks to support kids throughout the state.

Rebecca P. (00:59:52): Since March, more than 2500 of our employees have been working remotely. COVID-19 has created its challenges, but their spirit is strong and they are taking care of our members and serving individually in their communities, sewing masks, packing food boxes, packing hygiene kits in their homes, of course, gowned and masked and wearing their gloves.

Rebecca P. (01:00:20): The foundation is continuing to review grant applications and meeting those needs in the community and in the state. The company is continuing to respond to other needs in our communities.

Rebecca P. (01:00:32): Arkansas is our community. And as with any community, it takes everyone working together to make us better and improve the lives of our neighbors in the communities where they live, learn, work and play before, during and after COVID-19.

Rebecca P. (01:00:56): Thank you so much. I appreciate the time to present on this very important topic.

Caitlin Ellis (01:01:01): All right. Thank you so much, Rebecca for sharing Arkansas Blue Cross Blue Shield's leadership and commitment to the community during these challenging times.

Caitlin Ellis (01:01:12): I know we are up on 3:00 PM, but I would like to just take one moment to ask a question. We did have a lot of questions coming in around food waste and how to improve food distribution.

Caitlin Ellis (01:01:24): "Why is food insecurity increasing while farmers are throwing food away? What needs to be done to fix this distribution issue and how can we better help food banks obtain food that would otherwise be wasted?"

Gita R. (01:01:40): Well, this is Gita. Thanks for the question. This is Gita from Feeding America. That's a great question and it's definitely top of mind for Feeding America right now because, yes, we are seeing farmers having to destroy crops and throw out milk and things like that and that's very disconcerting when we are facing an increase in food insecurity and hunger.

Gita R. (01:02:05): There recently was a new program put into place by the feds called CFAP. Feeding America's national network worked with all of our food bank members to make sure they were included in that. This was not something that we could apply for from a national organization standpoint, but we made sure that all of our food banks were connected to one or more organizations in their communities that were going to be recipients of the resources from this program.

Gita R. (01:02:41): In our upcoming, our next call survey, we're actually going to be asking questions around the CFAP Program and how that has been, how that has affected their ability to source and distribute food. So I would love to be able to do follow-up with group and let you know what we're seeing.

Gita R. (01:03:04): That was our immediate response was to make sure that our food banks were included in the CFAP process and able to get some of these prepared meats and produce and dairy products to be able to get them out to our communities.

Caitlin Ellis (01:03:24): All right. Thank you for those comments. Unfortunately, we are out of time today. I would like to thank our excellent panel of speakers for being with us and sharing their work. We did have a lot of great questions come in, so we will compile those and send those off to the speakers if they're able to respond or think about the questions that were coming in.

Caitlin Ellis (01:03:44): Your feedback is important to us, so please take a moment to complete a brief survey, which can be found on the bottom of your screen.

Caitlin Ellis (01:03:51): Our next webinar is on Monday, May 18th where we will be looking at substance use disorder and growing concerns during COVID-19. You can register on our website. Thank you all again for joining us today.

Presentations

The Evolution of Food Insecurity & Its Impact on Communities

Daphne Hernandez

University of Texas Health Science Center-Houston

Food Insecurity, COVID-19 and the Community

Rebecca Pittillo

Blue and You Foundation for a Healthier Arkansas

More Related Content

See More on: Coronavirus | Social Determinants of Health