Webinar

Food Insecurity and Health: Strategies to Address Community Needs

Time & Location

More than 34 million people in the United States are food insecure, including 12 million children. Some groups facing disproportionately high rates of food insecurity include children, seniors, Black, Indigenous, and Native American/American Indian communities. Food insecurity has various causes which have been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, such as poverty and unemployment, lack of affordable housing, chronic health conditions, and racial discrimination.

This webinar explored the impact of food insecurity on health and factors reducing access to healthy and affordable food. Experts will discuss solutions such as community-based food system partnerships targeting vulnerable populations. Speakers addressed:

The importance of access to nutritious food to health and how food insecurity disproportionately impacts some communities across the nation.

Addressing the social determinants of health through partnerships with health care and community partners.

A health plan’s perspective on ensuring equitable food access, including a $22 million investment to support the Food As Medicine program in the US.

0:14

Good afternoon. I'm Cait Ellis, Director of Research Programs at the National Institute for Health Care Management Foundation.

0:20

On behalf of NIHCM, I'm thank you for joining us today for this important discussion on food insecurity in the United States.

0:27

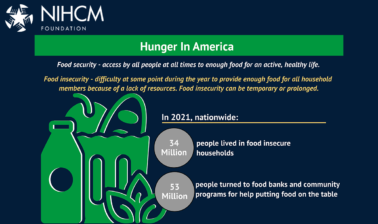

The most recent data from the United States Department of Agriculture found that 34 million individuals in the United States were living in food insecure households in 20 21 according to just over 10% of households.

0:40

So while most helps households have consistent access to food, there was a sizable amount of households had experienced food insecurity at times during the year, meaning their ability to acquire adequate food was limited by a lack of resources, rising costs, or other access challenges.

0:56

Today we'll hear from our procedures panel of experts to learn more about the impact that food insecurity is having on families and communities, the connection between food insecurity and health, and strategies to improve access to affordable and nutritious food.

1:11

Before we hear from them, I want to thank NIHCM's president and CEO, Nancy Chockley, and the whole team, who helped to convene today's event.

1:19

You can find biographical information for our speakers, along with today's agenda and copies of slides on our website.

1:26

We also invite you to to join the conversation on Twitter using the hashtag food insecurity.

1:32

I am now pleased to introduce our first speaker, Dr. Hilary Seligman.

1:37

Dr. Seligman serves as a Professor of Medicine and Epidemiology and Biostatistics at the University of California, San Francisco. She directs the Food Policy, Health and Hunger Research program at UCSF Center for Vulnerable Populations and the CDC's Nutrition and Obesity Policy Research and Evaluation Network.

1:57

In her work, she conducts research and policy evaluation focused on food security interventions and health care settings, federal nutrition programs, and income related drivers of food choice.

2:07

We're so honored to have her with us today to help us understand more about the relationship between food insecurity and health.

2:17

Thank you very much for inviting me to talk about this topic today.

2:21

I'm going to frame the conversation around food insecurity and health and try to tee up some specific strategies to address community. Next, right.

2:34

As Cait just mentioned to you, in 2021, about one in ten households in the US were food insecure, and this includes about 6.4% of US households that the USDA terms households with low food security. These are households in which the quality of food had to be decreased in order to meet a severely constrained food budget, and another 3.8% of US households who live in what the USDA turned to household with very low food security. And the need households that have even lower food budgets. Both the quality and quantity of food that has to be decreased in order to meet the budget.

3:14

Next slide.

3:18

There are substantial differences and food insecurity by race. These are the most recent numbers that have been released by the USDA which shows you much higher rates of food insecurity in Black and Hispanic population. These are the official numbers released by the USDA using their terminology. I think it's important to understand who is missing in this graph. Because there are also significant disparities between food insecurity rates and white population and food insecurity rates and Native American indigenous populations, as well as Asian subpopulations as well. And it's very important that we keep the population in mind as well. Next slide.

4:02

So, increasingly, when we talk about food insecurity, we're talking about food and nutrition security together, food security is defined by the USDA as accessed by all people at all times to enough food for an active, healthy life. Healthy in that definition is important and is part of the construct of food security. But the concept of nutrition security has really come into focus slightly as a way to put an increased emphasis on the importance of elevating not just food security, but diet quality and equity when we're talking about food insecurity in the United States. And so, I want to understand the term, nutrition security, and use that term, perhaps today's discussion, to really focus on diet quality. Because quality is really a primary outcome that we're interested in. We're when we're talking about food insecurity in the healthcare setting.

4:57

Ended up to elevate the importance of equity in all of this work. Although this isn't quite correct, I think an easy way to shorthand to warrant the way that this has been understood by many. As a shorthand would be that food security as having enough calories sufficient number of calories and nutrition security really focusing on making sure that those calories are the right kind to address the increase risk for diet related chronic diseases in everybody in the United States. But particularly in populations that are at the highest risk for food insecurity. Next slide.

5:37

So, when we're talking about diet related chronic diseases in the US, we have to hold high rates of food insecurity next to a number of other important risk factors that are impacting the dietary intake of low-income populations in the US. These together construct what we like to turn the dietary to buy. And it includes high rates of food insecurity, increased difficulty accessing nutritious food in low-income, and particularly in black neighborhoods. Because of lack of geographic access to full service grocery stores.

6:10

Unhealthy dietary intake, which is partially related to healthy foods, being perceived as luxury items because of their class. And we know that these factors together increase the risk of chronic disease. And that poor diet is the number one cause of death in the United States, because it serves as a factor for diet related chronic disease such as obesity, diabetes, heart failure, and other heart diseases, and this increase in health care costs. And this has been a primary motivation for the healthcare sector to have increased interest in addressing food insecurity in their own setting. Next slide.

6:52

Next slide.

6:54

So, one of the ways that we have tried to quantify the burden of food insecurity in the healthcare setting is to look at the additional amount of money on healthcare expenditures per adult person living in a food insecure households when you compare them to a similar adult with similar comorbidities living in a how competent secure. And if you multiply that increased expenditure, value on health care, which is about $1500 per year, by the number of food insecure people in the US, what you find is that we spend about seventy seven point five billion dollars annually on our healthcare expenditures that we think are roughly attributable to food insecurity. And this is one of the primary motivations, again, for the health care sector getting involved.

7:41

Next slide.

7:45

Now one of the questions that people ask us as well, can we save those seventy seven point five billion dollars by better investing in food security intervention? And one of the things that the answer to that question and acquired understanding is whether it's food insecurity is being increased healthcare expenditures, or whether increased health care expenditures by decreasing capacity. And they'll hold down a job increasing out of pocket health care expenditures and other out of pocket expenses.

8:15

Whether I'm being ill in the United States is just predisposing people to food insecurity, and I will say that this has been quite well studied now. And, the answer to this question is that both are true, but the primary arrow, the most potent direction of this relationship is food insecurity causing poor health and poor health driving an increase in healthcare expenditures and not that an increase in out of pocket health care expenditure increases risk for a household to become food insecure, Although this does happen to. And what this means from an intervention perspective is that, if we can address food insecurity with food security intervention, for example, in the clinical setting, we may be able to decrease adverse health events and decrease health care expenditures.

9:02

Now the poor health outcomes that have been associated with food insecurity are many, many, many. And I include some of those in the right and the right hand side of the slide. But the reason we can find associations between food insecurity and almost any health condition is because in some cases increase healthcare expenditures, increased rates of food insecurity. And that has really driven us to think of food security interventions, have health care setting to really be focused on diseases that are highly sensitive to diet and particularly the quality of diet.

9:35

Next slide.

9:40

I would have to address the overlap between food insecurity healthcare outcomes and Kobe 19. And I think that the pandemic has really highlighted the really important ways in which the diseases that are associated with food insecurity are increasing morbidity and mortality in the United States, and putting an extra burden, in particular, on low-income populations. All of the diseases, that food insecurity predisposes people too because of poor diet quality and other risk factors are highly related to severe outcome. Some covert 19 as well. And so it is true, that Coburn 19 morbidity and mortality with much greater for people living in food insecure households. And again, a place where food security interventions would likely have caused improved health outcomes.

10:29

Next slide.

10:34

What this has meant, and in a broader context to implement the export. Again, ask a question, do we need some re-alignment between healthcare and social care in the United States?

10:45

I'm sure that this graph is familiar to many, many of you and in this room. And it looks like when they change the slide, the arrow moves to the green circle should be around the US, not the UK. To move, in your head, that green circle over two bars to the US, where you can see that the US outside proportion of their health care spending on treatment of disease, rather than prevention of disease for social care. And you see that in the 16% of our health and social care. And 16% of our GDP is spent on healthcare, as opposed to only 9% of social cache. This is a drastic misalignment and compared to other countries and makes us wonder the extent to which we need to increase our spending on social care in an effort to decrease spending on health care. And that has been the primary motivator between what we call moving behind what we call moving upstream. Next slide.

11:51

And I wanted to be clear that moving upstream is a term used to talk about our capacity to improve community conditions. Are the root causes of disparities in the United States. And disparities, in exposure to social determinants of health, is at the top, the top part of the slide here.

12:13

And we're really talking about laws, Policies, and regulations that create community conditions, supporting the health of all people, where the health care sector has been engaged, is really in the middle area. The mainstream area of addressing individual social need. Perhaps the healthcare sector, we don't have the tools or the capacity right now to address these underlying systems and structures. But what we might be able to do is to screen people. For example, in the clinical setting for food insecurity and made sure the patient the patients who are experiencing food insecurity have access to the resources that they need to become more secure.

12:54

Next slide.

12:57

And because of this desire to move to the mid-stream area and to some of our interventions addressing food insecurity into the clinical setting, there have been a lot of studies that try to model out what this would mean in terms of health care costs. And I'll show you one example here of a modeling study that I've used to try to understand the impact of Healthy food prescription distributed through the Medicare or Medicaid program, which, in this case, was meant.

13:32

was defined as insurance covering about that, about 30% in the cockpit, healthy foods, fruits, vegetables, whole grains, seafood, plant oils, et cetera, and admits that E this incentive, innovation or subsidies, unhealthy foods would be cost effective after five years primarily by reducing the incidence of diabetes and cardiovascular disease. And this was modeled out to be more cost effective than many currently covered medical treatment. Again, reinforcing the potential importance in the healthcare setting, which is not a single study that's been done that shows that I'm elevating with one study. But there have been numerous, other modeling studies that show very similar impacts.

14:17

Next slide.

14:20

That is it for me, and I'm looking forward to your hearing about some specific intervention.

14:25

Thank you.

14:27

Great. Thank you so much, Dr. Seligman for sharing the relationship between food insecurity and health and really driving home the importance of nutrition security as well.

14:36

Next, we'll hear from Matt Habash, the executive Director of the mid Ohio Collective, a leader in the Feeding America network that is made up of five mid ohio assets working together to address the social determinants of health, the place, and often keep people in poverty.

14:51

Matt takes an active leadership role in the community, having served on numerous boards, and has received various roles, awards, recognizing his commitment to and work in, serving those most vulnerable.

15:02

We're grateful he is with us today to share his efforts to increase access to nutritious food through partnerships mat.

15:10

Thanks, Cait. Good afternoon, everybody.

15:14

I've had the privilege of being in this role now for, this is my 39th year, so I've seen the evolution of food banking from the very beginning. You know, in terms of when we were first starting out to what it's really stepping in today, which is really trying to describe the upstream conversations that Dr. Seligman just mentioned, I've had the privilege of working her on. a research project on diabetes within the Local Food Bank, Columbus area. Back in 2010 to 12. So, it really is a shift and a lot of the work. I think it's important to recognize that each food bank across the country is different based on what they do, but collectively, we're really trying to advance. You can go to the next slide.

15:52

Just to give you a sense, we shifted to begin a terrible timing, but we did it at the beginning the pandemic. And it really was around the idea of shifting from just being called the middle of a food bank to the Mental Health food collect, and I really was Ronald recognizing the assets, But more importantly, around, stepping into looking at our work differently, rather than just being an emergency food provider. We had a lot of other things going on, we really created a vision for many years. It was a hunger free and healthier community, and we really wanted to step into that work. So, the collective was really around these five circles, but probably at the foundation of that is the idea of right time, right. Place, right, services. And it really is how can we connect to our customers better. We shifted from client, the customer language, but it really was first with the food bank, which is what we're already doing. But we're into a very much data driven, smart response to how we do our work. We build a data tracking system, and I'll talk a little bit more about that in a second.

16:48

But, it really was around how to do that work that we're doing to make sure we could get the food where it needed to be. And it was also the right kinds of food and at the right time for our customers to be able to access it.

17:00

You know, the strategy now around that is the markets were building these little Ohio markets, which are 40 hour a week, multi-purpose facilities so that we can look at the whole person to really start to address some of those upstream areas that the Dr. Seligman mentioned. But it was really around making sure that we were open and available when our customers needed us to be, not, when it was convenient for the particular agency, to be in the space. We have a farm, which I'll talk a little bit about, It's a high-tech, urban Ag farm that we're building out, our middle, Ohio can kitchen motto, was really, we do the typical things that food banks do with after school meals, in summer feeding and those things.

17:39

But it's also now stepping into, can we cook some of this amazing food that we're getting and have it ready for customers? So think about it from a convenience perspective. And finally, the middle how pharmacy, this has been our connection from the beginning. When we first started to do the diabetes research back in 2010 to 12, and also we got asked the Columbus to lead the national effort to, in fact, find the next billion pounds of fresh produce and get it to food banks. Next slide.

18:08

So, step in this gives you a little sense of, you know, this is some of us, as I said, we're data driven. This is our 20 county area out of the ADA counties in Ohio. The next side, next to it, is a heat map of where the people come from to get services from us. You can see what the major dark spot is. The Franklin County, Columbus, Central Ohio area import the largest city in the country. Yet we have you know, a lot of other folks that are, you know, nine Appalachian counties, you know, small county, rural areas, that we also are trying to address. We can tell you this year, there were things are up considerably. We have 32% increase from 21 in terms of the number of fresh track as the data tracking. So, that's the number of visits that people are already up this year. Almost 45% in the last couple of months. We're seeing an overall increase of 20% for the whole year that's, over and above the pandemic numbers. So it's, it's the scary part of this.

19:00

And we have, this is probably the most amazing stat in 155,000 new customers, new families, that have come to get help for the very first time in their lives. Next slide.

19:13

You'll see from this, data is continuing decline. This is, you know, the numbers of people that we're serving are at record volume. This is the highest, I've ever seen it, it's higher than the peak of .... You know, when you think about the fact that all the benefits from ... ended and pretty much with the exception of the enhanced food stamp, still going on in Ohio to the fact that we've had no inflation. And we'll record price increases across the board, whether it's food, housing, gasoline, or sold today, gasoline went up another 45% a gallon based on yesterday's announcements.

19:45

Next slide.

19:47

This gives you a little sense. You know, we're in the cooking meals and what we're doing currently, you know, it's really around how many meals can we produce? This is for a variety of things, whether it's kid meals. Community meals were doing a lot of soup kitchen meals. Now, that are cooking that we didn't do before, this is all since the beginning of code that we have really stepped into this space about, can we have ready to eat food available and where it's needed stepping up when the shelters have the D concentrate, all the shelters during culvert?

20:14

And we're continuing to see all of the extra sites that opened up a lot of non emergency meals. We've taken over cooking for some schools, but it really is around can we take fresh food and get it to people with a state that's easy to consume. Next slide.

20:31

So, this is the middle of a pharmacy. This, for us, is really stepping into today's conversation for us. It really is looking at that mid point, the social determinants of health, and where we can play a role.

20:42

And I have to say, We're trying to reposition ourself as are some other food banks as a low cost, high value, healthcare strategy. Because if you think about all of what Dr. Seligman so eloquent just said, this fits right into that in the sense that we have surplus produce in this country, and if we can get it to people.

20:58

And then, because we have a data tracking system, we have the ability to match data with our healthcare partners, in this case, federally qualified health centers, that we're matching day, that we're tracking over 30,000 patients right now, in terms and seeing the health outcome. And if you use the modeling study out of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, it's suggesting that a one point drop in your A one C is an $8000 cost savings to Medicaid. If you give food banks a little bit of that money to continue to do this, then we could do it, you know, all the time.

21:27

The interesting thing here, you know, the most amazing stat in our data system is that 36% of the people will come once a year. 70% of the people come five times or less. So, this idea that people get free food and come all the time is simply not true, You know, the reality is, we get you come an 11 to 24 really closer to the twice a month. We're seeing the health care improvements and we're not controller for any other variables, were just make it readily good food available to people that are trying to manage their disease. In this particular case, it's diabetes. But we're really trying to address this and recognize, where can we step into this space. We just started a pilot with Weight Watchers where, basically, right. We've got early pilot was 75 families that were in the pharmacy program, really stepping into, to wanting to partner with what Weight Watchers and to really have a free program to allow them to avail themselves of all all of the work that's in Weight Watchers to help them manage their weight in this process Using the fresh food.

22:27

The pharmacy program is simply designed where the doctor writes a script. You know, we learned a lot out of that diabetes study. one of the things we learned was doctors don't even screen for food insecurity. So the idea that, you know, when you talk to them, they didn't know what to do with it, they did.

22:40

So we were connecting them, and we've really been able to connect the doctors rightest script into the data system when the particular patient goes and completes, you know, the produce picked up.

22:52

In this case, we're able to feed that, visit data back to the healthcare provider, and then eventually they sent us back data on health outcomes in an aggregate way.

23:01

So that's where we're seeing the real benefits of taking surplus fresh food and getting it to people just as they need it so that they in fact can you have better health outcomes. Next slide.

23:17

one of the things we're also doing in that space is really connect. And we've got a higher state here. So we're doing additional research with them, really trying to take a look at it. You know, somebody is to make sure they work This metal high Margaret, that's a picture of our newest market. You can only see a side of it. That's an actual 12,000 square foot convenience store that was only open for 18 months brand-new. We bought it in a high need area and we began to let people come. It's already the second busiest distribution in our system. It's open 41 hours a week, over at nights, weekends, you know, as well as during the day. People come in, they get the shop, it.

23:50

They're allowed to come back as often as they need to come back, because we're really trying to step into that space of having convenient hubs that are open when people need them to be regular access to the fresh food. So they don't have to take a lot of it all at once. They can come get it, they can use it, they can get recipes, you know. And we're even starting to look at how we use technology differently. So for us, this is really a step into what you're looking at is are the side is we just installed lockers as a refrigerated blockers where we can take the pharmacy scraped and put it in that lock, or the person can pick it up. You've got about 24 hours or so to pick up the product. They can come when it's convenient for them.

24:28

We're going to test this and, know, that site will eventually, I'd seen, if this works, we'll put it in some of our rural locations and ask one of our partners in that area to continue to have readily available, eventually, with an order ahead.

24:40

Online ordering system, that work that we've worked on nationally of Feeding America. Curbside picked up is what's currently going on, because of Cove at home delivery. You know, trying to meet the customer where they are, allowing them to get the pro and treat it like it's a grocery store. This looks like a grocery store, and we're currently in the process of opening a number of other these. Now, stepping into a lot of the other work in the one stop shop for us is really looking at kitchen prepared meals. Partner clinics, we have a lot of organizations that are partnering with us in this space to take a whole look at what the particular people need in that area. The first two customers came through, that seven, $9000 in benefits, they didn't know they were eligible for, whether it was for housing. For utility assistance, we're also able to where people that want to enroll in the pharmacy program, to get them connected, as well to healthcare, six slides.

25:32

Know, the kitchen for us, really isn't evolution from what we're doing for us, and if I had to boil all this down, you know, we're trying to make convenience, a healthy choice. You know? We run a restaurant where We cook healthy food, were feed kids at a day care, out of that restaurant, and the Boys and Girls Club all around fresh, healthy food.

25:50

So that, but another part of it is, can we take the food that we have, that's in bulk, that's produce, as I like to say, none of us go home every night and cook a meal from scratch. So if we give people a bunch of fresh fruit, and are a single parent, is really hard.

26:04

So can we take some of that food and cook it and have it ready to eat meals the same way we shop the perimeter of a grocery store? Can we put that in the markets? People can pick, pick it up, and in fact, take it home, heat it up and have a ready to good, healthy meals. So we're trying to make the healthy choice a convenient one. You know, we partnered on one of our first markets, was on Columbus State's campus, which is a 35 to 45,000 student downtown Columbus two year college letting those students our work and going to school and trying to take care of their families have ready access to food. We just bought a food truck that we're really going to take to the streets, take at the festivals, putting healthy food in front of people, showing people how easy it is to do this. But that kitchen will be a lot of grab and Go meals and we anticipate 23 as the start the first year will do over 50,000 servings. Next slide.

26:53

Ohio farms, we really, we started with 1 small 3 acre farm, because I like to say, I'm not going to find my way out of the hunger problem. The first year we did that, we grew £40,000 of produce, we gave away £30 million of produce several years ago. So we're prefer to have the food, the farm from around the country. That gives us the excess surplus, but we're using it as an education farm. What you're looking at on the left is how we leverage technologies. Those are growing towers are using very little water. I think it's five minutes a day, twice a day screen, growing a lot of leafy vegetables. You can grow a lot of things even in the five gallon top down at the bottom. You can grow some root vegetables, and one of these tires will eventually, you know, as we expand this, we have two farms that were setting up that will be able to, literally, teach others how to do this, Use it as an edge, a farm for kids. And, really, as an opportunity for your, where, food comes, we've got high tunnels. We will have greenhouses.

27:45

We will have hydroponics on this and it's all designed to use it as a farm incubator program to really train local farmers on how to increase yields in urban areas. a different way of dorne urban farming. With minimal water kinds of things, don't even need Dart. You can do this on asphalt and a lot of K to 12 education and community for food and nutrition education out of that farm.

28:08

So, that's the last of our assets. You can go to the next slide. But, but really, for all of this, if I had to boil all of this down it really is, and this is something that I'm much bigger fan of, using the language food is health rather than food As medicine, I know. That's a fairly common term, in my only simple reason, is somebody that's Not a healthcare provider, and, at least in the traditional sense, is that, at the end of the day, I'm really trying to impact people's health. That's what for us, as the new measurement is. And sometimes when I say food as medicine, it sounds too much like a drug, You know? As our system, I have to cure a hospital board for a number of years, you know, and we have a sick care model. How do we transform it to a health care model. We believe we can take healthy, nutritious food that is available in this country and get it to people in the right place, right time, right? Service, right suit model, In a way that we can impact our health.

28:59

And we have an ability with the data, to measure that. And we believe we can take why not take surplus fresh food And get it to where it needs to be, and have an impact on people's health?

29:09

So for us, my new measurement of success is simply to look at this, not just the amount of meals we produce, the pounds, the people served, what I call the widget counting. It really is to say, Can I have an impact on our customers health?

29:22

And that's where we're trying to drive our entire strategic direction.

29:29

Great. Thank you, Matt, for highlighting the value of community partnerships and giving us insights into the latest efforts in Ohio to improve food access.

29:38

Thing you asked me, a minute, it was that the dollar general, I forgot that, I'm sorry. Dollar. General is doing what a lot of retailers are doing. And that's simply is trying to take their excess product at the store level and get it to people. The beauty of dollar generals they roll this out across the United States, is the fact that they're in a lot of rural areas. So that hopefully, will provide some additional food, the same way a lot of other retailers across the United States don't want to waste their food. At the store level. We're connecting Direct Agency. So they can pick up that food and make it readily available to well. So you'll see more about Dollar General following a lot of the other retailers across the country and making sure that student does not get wasted.

30:19

Thank you. Sorry about that.

30:21

Appreciate it. Thank you.

30:23

Next, we'll hear from lands Chrisman, the executive director of ... Health Foundation. In this role, Lance leaves the foundation's mission to advance to advance health equity by improving health through strategic partnerships with community based programs that focus on maternal and Child Health, food as medicine and substance use disorder. We're so grateful to have Lance with us today to share ... efforts to ensure equitable food access Lance.

30:49

Thanks, Cait! You know, really appreciate the opportunity to talk a little bit more on the subject, and it's really exciting to be a part of this forum. I think Dr. Seligman did a great job in setting the topic of defining the size and scope of the issue.

31:07

And then Matt came in, and, and, which is Food, Ohio Food Collective, kinda give you an idea of some of the systems and things that are in place. And so my goal, you know, when you looked at the agenda, ensuring equitable food access is a pretty big piece of the pie. So what what I'd really like to do is just give me an idea from a corporate perspective and more specific to my role, a private foundation or philanthropic perspective on how we are attempting to address the topic and get to some of those. I'll start with a macro, and then drill down to some of the programmatic elements. So if you wouldn't mind, advancing to the next slide, please.

31:52

So at elephants health in our community health strategy, really aims to address those health related social needs, or some folks call them social determinants of health, through really using as much science as possible. evaluating data. And from that data, building evidence based interventions, so that we really want to be a part of the solution for health equity, I think that's the most important thing here. So that's, that says, at the broad macro elements health perspective. If you go to the next slide, you'll see that we really view this, and this is really for my own, how, I keep the buckets, straight. We look at two different pathways to achieve that. This, if you look on the right, you're going to have our business perspective.

32:40

You're going to have those folks that are driving to improve the health elements of our associates, Our members, and our community as a whole, also, on the, on the right-hand side. Where I'd really like to stay for this presentation is on the left-hand side here.

32:59

Our philanthropic efforts through our foundation. This is for, the broader community, needs it for the greater good of the community, And really driving home some specific whole health measures, not only for individuals, but for our communities as a whole. So if you can go to the next slide.

33:21

Get into some of the details.

33:23

Back in January of 21, we sat down with our strategy team at L events health. And we did a full audits of our Foundation approach, from, from everything, from our analysis, our social mapping, our evaluation of grant activity, to the dollars that we're going out the door, and what they were going to. And really, was a six month review, believe it or not. It was a very stringent review of everything that we were doing in the Foundation footprint. And the findings came back and they said, You know what, you're doing a good job, doing a very good job, but you're trying to do too much for too many. You're spreading yourself very thin.

34:10

And so the goal, or the feedback from this refresh, was, you need to run deeper and focus on some specific health outcomes in specific areas, and really run deep in those areas.

34:25

And so from that, we adopted a three year goal to spend up to $90 million and three primary health focus areas with an additional focus, obviously, at the time we were still and we still are in the pandemic. So we wanted to make sure we still maintain that focus on in disaster as well.

34:47

But for, for, the, the purpose of this presentation, we adopted a three year goal of spending up to $90 million on three primary focus areas: maternal practices, reducing substance use disorder. And then, the topic that we're really going to drill down on today, encouraging food is medicine, And I'm happy to say that that goal, and 90 million, we're going to exceed that easily. We're gonna blow right through it, and it's probably going to be between $250 million by the time we actually get there. If you can advance to the next slide, I'll show you why.

35:27

Drilling down into the food is medicine, although I do like Matt's comment on food is health, but we are a health care company, so when we do stick with the food as medicine.

35:39

If you could advance to the next slide, please.

35:44

There you go. So, specific to food is medicine, over the next three years, we're going to spend at least $30 million on the topic. And we've gone to an RFP process, meaning we define the specific geographies that we want to address food. As medicine. We also define the specific health outcomes we would like to see for the specific demographics. Then, we submit an RFP into the community and have our non-profit partners respond back. If they have a program that states, If you can go to the next slide, you can see, over the past year and a half, we've already secured about $23 million and committed $23 million in grant activities.

36:32

So, halfway through, we've already at about 80% of the resources committed. You'll see, those are, as I mentioned. We have specific health outcomes related to reducing food insecurity. We want to make sure we're addressing those specific health outcomes, such as reducing BMI, reducing hypertension.

36:57

There are specific measures with each grant that we're looking at, and so you'll see some of the categories there that that we utilize too to get there.

37:08

Next slide, please.

37:11

This is what I really want to dig in on. So what?

37:15

Just to give you an example of a couple grants in the area. And, you know, at the beginning of this pre the forum, they were kind enough to say they had assembled a panel of experts, and I would absolutely say Matt and Dr. Seligman are absolutely experts. And I'm just I know just enough to be dangerous. But I do know to surround myself with experts. So specifically to to kind of give you the six degrees of separation Dr. Seligman was instrumental in helping us shape this grant to Feeding America. This is absolutely the largest grant in the history of our foundation. It's a $14 million grant over three years.

37:55

And to continue with that six degrees of separation, Matt, one of our major entities that is implementing the program is the middle Ohio Food Bank which is part of Matt's Collective, so small world, but once again, we like to surround yourself with experts. And this is a great form. This is our third iteration of the food is Medicine Program. The first iteration really spent the time on screening the patient's creating the intervention. And so with food as Medicine three, we're really spending more time in drilling down on collecting the data and tracking the data and and conducting the evaluation seeding.

38:41

America's brought on third party evaluator to help us look at the data dig deep. Once again, you heard me say at the onset uses much science to the R of this grant giving and an impact that are attempting to create. So we're really excited about this grant just scattered off the ground earlier this year. So we really look forward to watching the impact over the next three years with respect to this, so that's that's at the national level, to give you an idea of a local grant to wouldn't mind going to the next slide.

39:21

A great organization here, actually in Indianapolis is local initiatives supportive support corporation or less. We sat down with them and created two point four five million dollars grant over the next three years to help address equitable food access and needy. Indianapolis neighborhoods were really utilizing and sitting down and bringing together residents, community leaders, experts on the topic, and civic organizations to analyze the local issues. Look at the local resources that are available, and develop achievable strategies to help address the cause.

40:07

And I just noticed, I volunteered at, uh, community garden on Saturday, and it was actually this community garden that's that's featured there. I didn't realize that was a photo of it that's called Alison's Garden. And it's in a food desert here in Indianapolis.

40:23

And they have basically two residential lots that they have no community garden on that is generating food and distributing within that community, into food deserts there. And and beyond. So great model that that is really getting at the grassroots level and leveraging the resources that are that are available in the local community. So we're pretty proud of that, that local grant. So just two examples of some grant activities that we are engaged in. As I mentioned, we have $23 million and commitments so there are many, many more across the country. But these are two that I thought really highlighted some of the programatic efforts that that we're attempting to put in the community to make a difference. Next slide. Please.

41:21

But it's not all just about the money. You know, we want to be a good community partner. So we've made those philanthropic commitments, but we also want to engage our associate base in volunteerism our associates volunteer year round. But just before the holidays in the September and October timeframe, we spill into November a little bit. We generate or create a program called El Events Health Volunteer Days, where we actually structure over 100 planned projects in 30 plus markets across the country. And that we target food, insecurity with all of these volunteer opportunities. That's what I was doing on Saturday. As a matter of fact, as part of the element itself, volunteer days. And so we engage our associates get out there.

42:14

They roll up their sleeves, get their hands dirty in, you know, that food banks, collecting and sorting, and packing food, and distributing those community garden, so on and so forth, We really use the volunteer days as a springboard into the holidays. And so just through the volunteer days, we, this year, we solve are 15,000 volunteer hours from over 1500 volunteers. Now, those are our associates. But we also use this, we invite their families. They invite their neighbors, friends. We really use it as a community building opportunity, and culture. Building opportunity, at the same time. And this, this just adds to, as I mentioned, we volunteer year round. We're going to have over 120,000 volunteer hours. Some structured events like this in 20 22. So you know, are our associates coven had them on the sidelines for a couple of years?

43:15

Because of the mass mandates and and weren't able to get out there, and, and volunteer. So now, they're hitting the ground running, and making up for lost time. So, we're glad to see it. So, that's really it. Next slide. Really, once again, thanks for the opportunity, just to give a few examples of what we have in place, and I look forward to the Q and A session.

43:42

Great. Thank you so much, Lands for highlighting Elements as Leadership in supporting community health and food as medicine programs.

43:49

We'd like to use the remaining time to engage in a Q&A session with our audience. So please continue to submit your questions in the Q and A tab, and I'll ask all of our panelists to come off of mute, and you can all come back on video.

44:03

So we've had a few questions come in around addressing inequities. And so I wanted to kind of put them out there for anyone on the panel to speak to. really what kind of research has been done to show that poor social determinants of health have a negative impact on food insecurity and poor health outcomes in a variety of communities around the country. So, specifically asking about data related to urban rural communities are counties that have higher underserved populations. Where can one look for that data? And if anyone can just speak more to kind of addressing those inequities, particularly in urban and rural communities.

44:44

I'll open this up to whoever would like to take it first.

44:48

Matt, do you want to talk about it in Ohio?

44:51

I can talk about it briefly in Ohio, but just a little bit, you know, from a Feeding America perspective, there really is a very strong current development around how to deal with equity. And across the country, I mean, it's to banking historically, has been kind of inequality model. Everybody gets their fair share of what we have to spread out, and now we're recognizing that the individual food banks are more resource than others. And, you know, so for us, I mean we have a unique service area, 29 Appalachian counties, I have the 14th largest city in the country. one of the fastest growing counties in Ohio, so it's a unique mix of the country. But there's a real emphasis on equity. We're trying to explore what that means in a health equity world. How do we get fresh fruit? Because it boils down to cost, a lot of money to move produce around the country.

45:41

And if you're a small food bank in a rural area, that's really difficult. So, we're trying to step into that space to say, how do we help each other years ago? We built mixing centers, so small food banks could mix up a semi load, not take an entire semi load of one product, which they could not do.

45:55

So, we're learning more and more in that space, really trying to address it, you know, from how do we take this product that's in various parts of the country and get it to where it is needed? And acts that match that up against the limited resources? So we're looking at it if the resource poor. How do we step in and help more than what they normally would have gotten a fair share to the data? I'd have to turn it over to you.

46:19

Hillary? Yeah, well, it's an excellent question. And as far as rural urban goes, there are many, many food insecure people in both rural and urban communities and suburban communities as well. And one of the things that we try to hold in mind is that there are food insecure people and every in every county in America. Although people living in rural and urban environment are both at higher risk of food insecurity compared to people living in suburban environment, the coping strategies for food insecurity can be a little bit different and those two communities.

46:57

And one of the things that I think that helps us focus on it opened the challenges are different and urban and rural communities but also that the opportunities for addressing food insecurity may be a little bit different. And urban and rural communities. And when we when Matt talked about farming, for example, we're not going to form ourselves out of the food insecurity problem in the United States.

47:23

There's no way for an individual rural person, maybe this could be important coping strategy.

47:35

Great, thank you.

47:35

I am sorry about went out a minute Yeah, We could hear you. Can. You can hear me, OK? Great. Inequities, in general, like, it sounds like you're getting a number of questions about equity and food insecurity in general. I elevated the racial inequities that we see in food insecurity. There are many other inequity households with children, particularly young children are at higher risk of food insecurity. Household headed by single parent are much higher risk of food insecurity and in particular household with people who have a disability which is really important when we're talking about food insecurity in the healthcare space. So we are working really diligently to try to create programs and systems and especially policies that will help in particular, those populations.

48:30

Excellent. Thank you.

48:32

one other question came in, do we have any long term information on individuals who've been prescribed healthy food?

48:41

So looking at kind of the long term impact of this approach, and if people when perhaps they are then able to afford healthy sort of later, do they continue to maintain a healthy diet after they've transitioned?

48:59

I'm going to take a stab at it. Fits into the research question. The largest experiment we have is the snap program, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, formerly known as food stamps. It is very clear that snap is highly effective at reducing food. insecurity rates reduces food insecurity by about 20 to 30% and by increasing people's food, budget allows people to afford a healthier mix of food.

49:24

Very good data shows that when people enroll in the snap program, let's start with children. When children enrolled in the program, they're less likely to become obese over time. They're more likely to graduate from high school. They're more likely to become economically self-sufficient and they're less likely to develop diet related chronic disease. Over subsequent decades of their life is really important and the strongest data we have. We also have data from the WIC program that shows that children who are exposed to these interventions to healthier foods do better, and their mothers do better when they are consuming those foods when they're pregnant. So that's our best data from the perspective of large national programs. Individual programs that are implemented on a local level are much more challenging to show impacts in terms of prevention of specific diseases. Like diabetes studies, Just long enough, and they don't go on.

50:22

They don't offer services for long enough.

50:26

But the small studies that we do have a really promising that they have the capacity to have the same impact on health outcomes if we were able to sustain them for longer. one of the reasons to really think about bringing healthcare to the to the table in a very meaningful way is we need strategies to help support these types of interventions. And it will go on for a duration that would be sufficient to help prevent or manage a case of diabetes or a myocardial infarction or a case of congestive heart failure. These things add up really quickly in terms of healthcare cost.

51:02

one of the things I would add to that, you know, to pick up on the Snap thing, is, several years ago, we were lobbying on the Farm Bill.

51:09

And we took healthcare executives and a doctor to lobby in the Washington, and it was kinda, the first acute, confusing to the Senators and Congressman Water, you bring in health care in here. I said, Because we need to rethink snap from an entitlement.

51:24

We all love to hate to good public health policy.

51:28

And we got our senator to actually use that on the Ag floor.

51:32

You know, to really look at this differently, because the data isn't there, that this will make a huge difference in this country.

51:42

Great, thank you.

51:43

Another question came in, What is the most productive way for a food bank or food pantry to convince healthcare professionals to screen and intervene, to issue healthy food prescriptions, et cetera? Many healthcare professionals just don't seem to have enough time to add this to the normal practice areas, So how do we really encourage them to make that connection.

52:05

I'm gonna be out of my element here a little bit, but I know there's some way of getting it into the charts. And like I said, let me can fill that in in terms of whatever that I see.

52:14

Charting that you do but to really get food insecurity recognized.

52:18

Even my own doctor, they asked the question, you know, when I go in and, you know, are you or anybody your household food insecure and I finally asked them, so we didn't do with that.

52:27

If I say yes or no, and that was really helping. one of the things we learned that diabetes research we did with Dr. Seligman was that doctors didn't screen.

52:34

Once they did, they needed a data someplace to refer people to. So, there was a step in that, you know, to do that, it's not easy, It's local and I think, you know, Feeding America, we've been working on what's the national strategy, and the reality of it is to meet, health care is local.

52:49

Know, and how do you get doctors, we think by continuing to look at their patients differently. I chaired a hospital board at the very end of that was right. When the term was when the ACA was coming into play, and they give me the entire checklist, or where they don't want you back and make sure they're doing all the right things. So they don't get you back. And I looked at all the doctors in the room, said, How was this plan gonna work if you don't ask any questions about?

53:12

If you're not asking them whether they have an I don't care what your income is. Your ability to prepare it, to acquire it, to bring all that in the salt, predates the pandemic, and all of us being able to online order. So, there's better solutions today for a lot of people, but it's in that space, that we've got to continue to build this connected connection, that healthy food matters, you know, my counterpart and San Antonio Coin, so who's going to pay for the food prescription?

53:36

If you're a social determinant of health work in health care is simply making a referral and you get paid for the company that does the referral gets paid. But nobody helps pay the health care bill at the pantry level, at the food bank level. There's a limit to what we can do with charity.

53:53

Food is there. We've got to continue to build the connections to this. You know, we've been able to show it, It's, it works. We don't have long term patient, because we don't see people all the time. It's not like you're coming back to see your doctor, but it's in that space that I think you can build connectivity.

54:09

We're gonna partner, when we open up a new market, we have 2 primary 1 federally qualified health centers right next to the market so that we can build that connectivity, higher states, building another facility, and we're connecting food into that health care strategy.

54:26

I'll add a couple of points from my perspective. Number one, you need a clinical champion. You absolutely need a clinical champion. It can be a physician, it does not have to be.

54:35

And the second is that you need structures and workflows set up within the clinical setting to make this work.

54:41

If you just throw in another bunch of things for the providers to do, for physicians, to screen for food insecurity and then figure out how to connect patients to community resources. It's not going to work, but if you make a system and a functional workflow, this is where we've seen must be really powerful. And the finally final thing I'll say is, it does not have to be the physician who does the actual screening for food insecurity, and actually, best practices suggest that it probably shouldn't be. Patients report that they are much more comfortable disclosing and discussing food insecurity with people who aren't their physician, nurse, or nurses or center, the front desk staff. So what we generally say at the best practice is that physicians or other health care providers in the case of it being a nurse practitioner or physician's assistant should follow up on every positive food insecurity screen. But they do not need to be the ones who are tasked with doing the screening.

55:45

Great, thank you.

55:47

We had a question come in around stigma. So how do we work to break the barriers to support health and reduce stigma in the areas of food insecurity and social determinants in general, really?

56:01

A good start but appropriate break. to me, stigma and stopping judgement are two sides of the same coin. But we really need people to understand that there are people in this country that are struggling, you know, big time and it got exposed during the pandemic.

56:18

And so, you know, the idea of our market strategy is it looks like a grocery store, it feels like a grocery store, you're invited in, you get to shop, we tell you to come back. You know, that's the opposite of model that we used for decades and food banks and food pantries where we give you a three day spot, never see again you know, kind of things that solve all your problems. No, But the ideas come, this is Fresh Food: Come Get, which you can use, Nobody's judging you for all those 145,000 families that we've helped that have never ask for help. Before.

56:46

That, Was really hard for them to cross the threshold of a free food distribution and get food. But recognizing that we're there, it's there, you know, we have the food, we want you to come get it, and we're not judging. So if we could all just stop judging each other, and just step up and help, I think we will reduce.

57:08

I appreciate this question in particular, because it gives us a chance to acknowledge the fact that we are coming to the three people who buy our titles, and by everything, in the way we present, are clearly very privileged people. The best way to get rid of the stigma in this work is to stop being privileged people creating the solutions, and to allow many, many more voices into the table to start creating solutions with that. Or even be responsible for the solutions that they think work for their own communities. And that, I think, is where we are all headed. I wish we had some voices on this panel, of people, who were able to create, or, or, communicate those, experiences from, from, a more personal perspective. There are, many, many policy solution that, we advocate for, that, have changed.

58:05

Then, nuance, and even been ditched. And we've started over because, the way that we understand the policy solutions may be different from the people who are experiencing food insecurity, and we have to be able, and willing to allow those voices to be heard, if we're going to get rid of these issues.

58:24

Thank you, Thank you for that. I think we have time for one more question. And, really, you know, we have such a broad audience, and so had some questions, And around how people can get involved was, you know, what are some of the ways to encourage an organization to get more involved? Or the easiest way to get more involved yourself in terms of helping out in your community.

58:46

Yeah, so many ways, first off, I'm a firm believer in, volunteerism get out there, get involved, get engaged, and when you volunteer organizations, find a way to get even more involved, you know, volunteerism serve on a committee, serve on a board, you do different things along those lines. I think the topic, when you look at it as a whole, can seem so big. And so all you can do is make a difference where you're at and create that ripple effects. So I, I start with volunteerism. I think that's a great place to begin. But then also, look at your different networks and resources. What is my company doing? How are we engaged on the topic? Are there things that we can be doing from a philanthropic perspective or from a business perspective? But first and foremost, in my opinion, volunteer.

59:42

Great. Thank, oh, yes, go ahead.

59:47

I think you're still on mute.

59:52

I really like that. and I think we all need to examine the places where we have power and use that power towards food security. And one of those places is by calling your own elected official and supporting good food security policies in your own community. Calls to our local elected officials can be extremely powerful, so Those, but also, use the power of your e-mail and your phone as well.

1:00:20

Great, thank you so much. Unfortunately, we are out of time. I would like to thank our excellent panel of speakers for being with us and our audience for joining us for this discussion. Your feedback is important, so please do take a moment to complete the brief survey that you will see on your screen. And also check out our website to see what other resources are available, including our recent infographic on hunger in America, and the registration information for our next webinar, which will be on the relationship between health and incarceration. Thank you all for joining us today. We really appreciate it.

Speakers

Hilary Seligman, MD, MAS

University of California San Francisco

Matt Habash

Mid-Ohio Food Collective

Lance Chrisman

Elevance Health Foundation

More Related Content

See More on: Social Determinants of Health